Does Anything Good Come From International Trade?

On April 2, 2025, “Liberation Day,” President Donald J. Trump presented the world with his list of tariffs to be applied to virtually all nations. This was the climax of a process that he had begun a couple of weeks before. He aimed to reduce the annual trade deficit that the United States has endured for years.

Reciprocal Trade And Tariffs (The White House, February 13, 2025)

Sec. 2. Policy. It is the policy of the United States to reduce our large and persistent annual trade deficit in goods and to address other unfair and unbalanced aspects of our trade with foreign trading partners.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/2025/02/reciprocal-trade-and-tariffs/

The worldwide reaction was swift and decidedly negative. Financial markets around the globe fell as investors and consumers alike worried about future price increases and potential shortages resulting from the new tariffs.

No doubt, the President and his administration anticipated this reaction and appeared more than willing to negotiate. To make a “deal” in the parlance of the President.

The Administration’s Economic Advisors, Scott Bessent, Peter Navarro, and Howard Lutnick, among others, agreed with the President’s view of trade. It was a two-dimensional transaction in which one side was winning (chiefly China), and the other side was losing, principally the US.

By now, everyone is, no doubt, familiar with the ongoing public debate over whether this new policy will harm or help the economy. We will leave that discussion to others.

However, there is another dimension to these trade transactions that is rarely, if ever, discussed: those trade dollars that return to the United States.

A New Kind Of International Trade

Just as 2025 is shaping up to be, 1973 was also a watershed year, one that greatly impacted America’s international trade for nearly half a century. 1973 saw the Yom Kippur War between Israel and its neighbors, with the US solidly supporting its Mideast ally. It was also the year that President Nixon took America off the “gold standard,” no longer would dollars be convertible into gold. These two factors precipitated an “Oil Embargo” by the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries, OPEC. Led by Saudi Arabia, these primarily Middle Eastern countries stopped selling oil to America.

For Saudi Arabia, this was the culmination of a strategy that had seen that country assert control over the massive ARAMCO oil conglomerate, Saudi Arabia’s chief oil producer, and a joint venture between major European and American oil companies and the sheikdom.

When the Oil Embargo hit, it was a desperate time for the United States, which descended into economic chaos, marked by long lines at gas stations and widespread job losses. Indeed, for the Saudis, the United States was far and away their most significant customer, and an immediate compromise between the two was needed.

US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger devised a plan that allowed the Saudis to control ARAMCO and, by extension, all of the exported oil, but with the caveat that Saudi Arabia must sell its oil in US Dollars. What became known as the “Petro Dollar.”

At first, it appeared that the United States was the real loser; after all, American companies had lost control of ARAMCO, the world’s largest oil producer, while gaining very little.

However, over the years, the scope of the Petro Dollar grew and grew. Remarkably, most of those newly minted Petro Dollars returned to the United States in the form of investments. After all, the US has the world's largest, most reliable financial markets. So, while many saw only a loss in ARAMCO ownership, few realized that many Petrodollars would make the round-trip, returning to bolster our financial markets.

So, while the oil companies took a hit, the financial markets gained a new investor — recycled Petro Dollars.

Around the same time the Petrodollar was created, the Nixon/Kissinger team also began trade negotiations with China. While it would take several decades for this relationship to mature, the “Petro Dollar” trade model was well established.

While there was no formal agreement (unlike the Petrodollar), the US insisted that all transactions be conducted solely in US Dollars. This created a similar recycling currency to the Petrodollar. The US paid for Chinese-made goods in Dollars, and subsequently, China returned, at least a portion of those Dollars, as investments in US Treasuries and other financial securities (stocks, bonds, etc)

International Cash Flow

While the US Balance of Trade, narrowly defined, presents an unflattering picture, there is another perspective that offers a somewhat more positive outlook. It’s what economists refer to as the “Current Account,” what accountants call a cash-on-cash basis accounting. The Current account reflects both the total money flowing into and out of our country.

Each month, the Bureau of Economic Analysis prepares the Balance of Payments Report. You can find it here:

https://www.bea.gov/news/2025/us-international-transactions-4th-quarter-and-year-2024

Now we know that last year (2024), the United States Trade Deficit was $1.13 trillion; that is, we purchased $1 trillion more internationally than we sold. Were there any other transactions last year that we should take note of?

The answer is a resounding yes.

Last year, we acquired more financial assets globally than we sold, by $1.4 trillion, to be exact. Our banks gained $25 billion in new foreign loans and deposits. Our financial companies, funds, and brokers gained $323 billion, while non-financial assets (including institutions, foundations, and private equity) rose by $507 billion. The US Government sold $574 billion in primarily US Treasuries of various maturities.

Of course, this counterflow of funds and investments did not offset our trillion-dollar trade deficit. The President is correct when he states that we need to reduce the trade deficit to a more manageable level or, ideally, eliminate it, thereby achieving a truly balanced trade environment.

However, the US Dollar’s status as the primary trading currency (the Reserve Currency) gives us a significant advantage over all other nations in gaining financial investments and deposits. For China, like our other trading partners, it was simply more convenient to leave their trade deposits and receipts in Dollars. Why convert back and forth between the Yuan and the Dollar when purchasing a US Treasury will provide a handsome return, and avoid any exchange risk? The Dollar thereby became the default settlement and investment vehicle globally.

The next step was for the US to open its financial markets to offshore investors. This created an opportunity for US companies to appeal to investors they might not have otherwise reached. A completely new investor entered the American financial markets, enriching us.

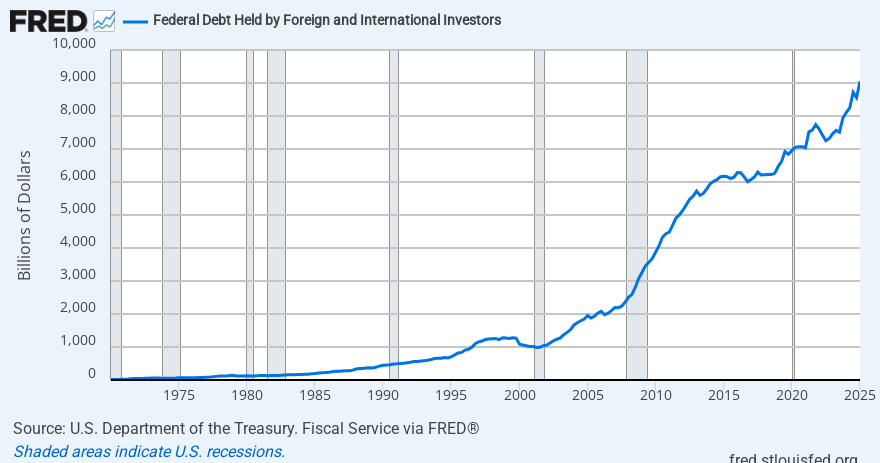

The most obvious example of our new financial strength has been our ability to finance our out-sized government debt. A debt that currently exceeds the total of our annual economy is generally a warning sign. But did you know that foreigners have helped us finance Washington’s spending by purchasing one-quarter of all US government debt? Without those offshore investors, it is doubtful that we could enjoy the relatively low-interest rates and continued spending of the federal government’s plans and programs. If we value those social programs and robust defense and protection, we ought to be more concerned about losing our offshore benefactors.

Then there’s our stock market, estimated to be currently valued at $52 trillion, by far the most significant financial marketplace in the world. It enables us to finance innovative technology, as well as develop leading-edge products and services. Lacy Hunt, PhD, formerly a Federal Reserve Economist and currently an advisor to Hoisington Management, estimates that offshore investors have placed an astonishing $18 trillion in our financial markets. An amount that’s more than double their investment in the Federal Government, and one of the chief reasons we’ve enjoyed such positive stock market returns.

Add it all up, and to even the casual observer, it becomes readily apparent that the United States’ relationships in global trade and finance extend far beyond the simple purchases and sales represented by the Trade Balance.

The Petro Dollar model of returning offshore currency has provided much of the financial miracle that is modern America.

References:

https://www.bea.gov/sites/default/files/2025-03/trans424.pdf