JP Morgan Chase Revives An Old-Time Investment Risk

It was a simple executive-change notice, the kind that dots the financial press nearly every day. Todd Combs, one of Warren Buffett's senior managers, would be leaving Berkshire Hathaway to form a new unit at JP Morgan Chase. But this was far from an ordinary management change. For the first time in nearly a century, the fabled House of Morgan would invest its own capital in the stock market. A move many considered far too risky for a commercial bank. And one that the US Government had outlawed for 66 years.

Comb's new position will be as the head of the revolutionary, all-new Strategic Investment Group. It's not often that someone can begin an entirely new division at a bank as well-established as JP Morgan, but there's a reason that the bank, up to now, has not ventured into the direct investment world. A reason that's replete with much of our country's investment history.

You see, until 1995, what Combs and JP Morgan were engaged in was illegal, forbidden by federal law, and punishable by fines and jail time. So how is it that the largest bank in the nation is now embarking on such a venture?

Our story begins a century ago. The time was the 1920s, labeled the "Roaring '20s" chiefly because of the good times that investors and speculators were experiencing. Like today, the financial markets seemed incapable of declining. Up, up, and away was the destiny of nearly every portfolio - fortunes were made on the heightened financial speculation of the time.

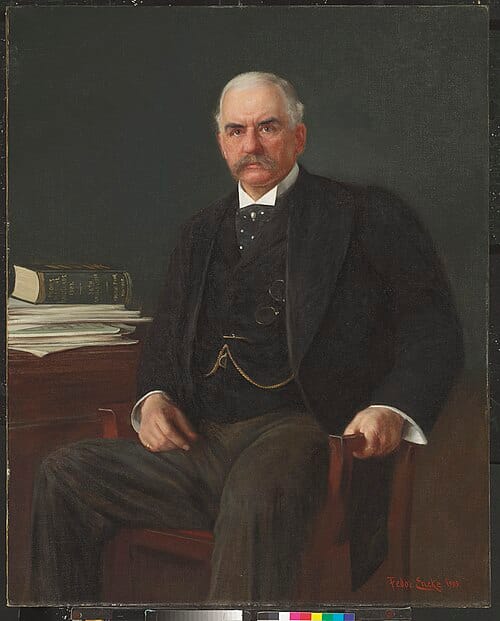

At the very epicenter of this financial euphoria were America's Banks. The banks were delighted to provide funds for the purchase of any new issue that might strike one's fancy – money was plentiful and available to almost any investor. And why not? After all, the US Banks were rock-solid, backed by some of the most astute financiers in the world, especially one John Pierpont Morgan.

Morgan was the most famous of all bankers, his reputation built on a history as the ultimate protector of the American Banking System. After all, during the Panic of 1893, it was J.P. Morgan who organized his fellow bankers to supply gold to the US Treasury after the Government nearly ran out of its reserves. Again, during the 1907 Panic, it was Morgan who organized a private-sector bailout for banks across the country that were on the verge of failure.

Now, there are two principal reasons that a bank fails. Generally, it's the bank's loan portfolio that gets it in trouble, and here the issues are either that the borrower cannot make their loan payments or the underlying collateral loses value. Of course, any collateral may decline in value, but it is especially true of financial assets. One reason for Silicon Valley Bank's recent failure was the decline in its "reserves" (or collateral), which were mainly in US government Bonds. These Bonds declined as interest rates rose in 2022 – 2023.

While the world has changed dramatically in the 116 years between the Panic of 1907 and the failure of SV Bank, the fundamentals of banking have not. If bank customers demand their money from the bank, and the bank cannot deliver, the bank has failed. Back in the day, it was Morgan and his organization that bailed out the banks; today, it's the Federal Reserve.

It was the Great Depression of the 1930s that showed the real impact of massive bank failure, failures like the country had never seen before or since. It is estimated that 9,000 banks failed during the Depression. Remember, this was before any bank insurance or backup of any kind. If you had your money in a bank, checking, or savings account, you lost it all. Ordinary citizens who felt they had a comfortable nest egg at the local bank were wiped out overnight. The impact was devastating, perhaps more severe than the 1929 Wall Street Crash.

Imagine waking up one morning to find that all of your money was gone. What would you do? Of course, you would no longer be able to spend. Spending would stop completely, and you would curtail trips to the grocery store and other stores. This decline in everyday spending rippled through the economy, eventually bringing the entire consumer half to a halt. The country could live without Wall Street, but not without the banks. With so many community banks shuttered, the nation's commercial activity ground to a halt.

Although the particular circumstances of each bank failure were unique to that institution, the fundamentals remained the same – a bank without sufficient reserves (collateral) is bound to fail.

As the 1930s crisis unfolded, Washington initiated a series of reforms designed to prevent another financial catastrophe. Among these reforms were the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Securities Acts of 1933, 1934, and 1940, which established the operations of exchanges, the issuance of new securities, audit rules, and mutual fund requirements. The most far-reaching and essential securities regulations ever, and a major contributor to the financial prosperity that we've enjoyed for over a century.

Most relevant to today's discussion was the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act. The US Congress recognized that the massive bank failures were a chief contributor, perhaps the major contributor, to the 30s Depression. The Glass-Steagall Act was explicitly designed to protect banks, a point often missed today. Congress wanted to prevent bank failures.

Although there are many specific provisions within the act, the US Congress identified one issue that was the catalyst for many of those bank failures – the confluence of stock speculation and conventional banking. The 1929 Crash clearly demonstrated that using stocks as collateral entailed tremendous risk. Banks ought to avoid the risk inherent in the securities markets.

So the Glass-Steagall Act created two types of banks: Investment Banks and Commercial Banks. Let the stockbrokers handle investment risk, while the bankers handle commercial risk. This demarcation between the two banking functions would reduce the overall volatility of the nation's finances. And most importantly, it would remove an element of systemic risk from the commercial banks.

Today

Twenty-six years ago, on November 12, 1999. President Bill Clinton signed the Financial Services Modernization Act into law, which, among other things, eliminated this divide between investment banks and commercial banks. You may have seen the stockbrokers who now work in your local bank branch.

Although it's been a gradual transition, as two very different cultures, commercial and investment banking, have come together, we now find ourselves in the same place we were a century ago, before Glass-Steagall – with investments, savings, and checking accounts, as well as loans of all types united under one "banking roof." It's the "Financial Super Market" that so many in the industry have dreamed about for years.

For the banks, just one step remained. Up until now, the leadership of most Commercial Banks has sought to maintain an arm's length relationship with their brokerage subsidiaries. Even Bank of America always made sure to distinguish its core business model from its Merrill Lynch subsidiary.

However, when Todd Combs sits down at his desk at 270 Park Avenue, the final hurdle will be crossed. JP Morgan Chase will begin investing its own capital in the financial markets. However, other divisions within the bank have been investing for years. It marks the first time that a bank as significant as JP Morgan will do the same. JP Morgan will now be fully integrated with all forms of capital investment – from stocks and bonds to derivatives, futures, and various exotic financial instruments. All this while retaining FDIC insurance. It's investing without risk, or at least with the US Government's Insurance against risk. How could that go wrong?

We rely upon the senior executives at our major financial institutions to set the fiduciary standard for guiding our country's finances. However, those standards are subject to change reflecting current economic conditions. What was considered reckless and risky immediately following the 1929 Crash is now considered overly restrictive. Limiting our banks' access to profitable new operations, such as investing in the securities markets. It's a move that reflects reliance on the multi-year bull market more than potential risk.

Only time will tell if this strategy will protect you and me, the everyday bank customers.