Out Uneven Path To Dow 50,000

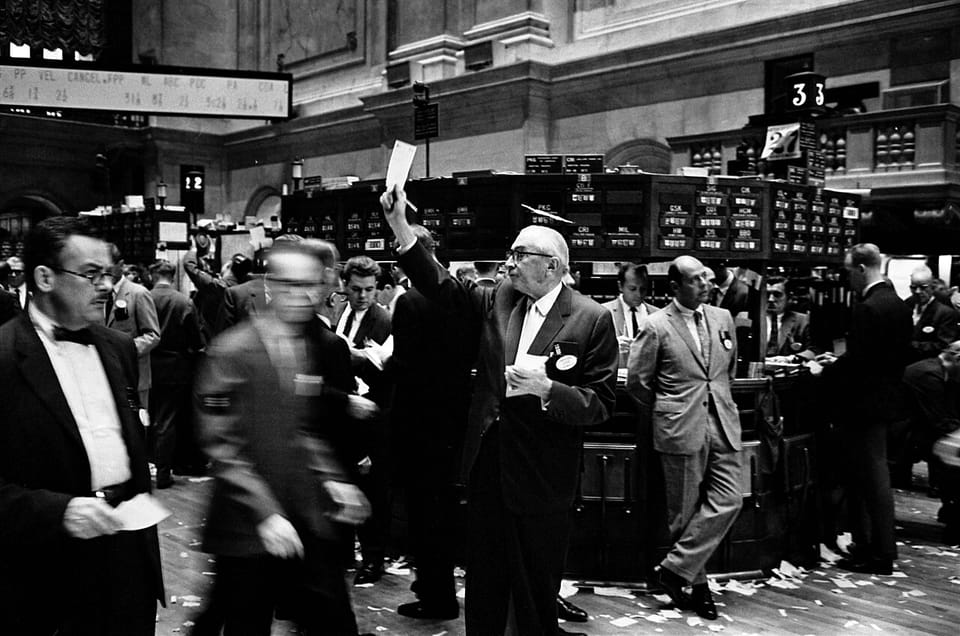

Something eerie happens when the stock market reaches a large round-number level. The first time I observed this phenomenon was in 1972, while I was studying at the New York Institute of Finance, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average surpassed 1,000.

People went wild, New York City was ecstatic — “happy days were here again” as the old song went. It was the ratification of American exceptionalism. It was as if our team had won the Super Bowl, the World Series, and everything rolled into one. Our scoreboard, the Dow, just showed that we had won.

Unfortunately, what most people, outside a select few on Wall Street, missed was that this “accomplishment,” surpassing the Dow 1,000 level, was the result of an old pattern we had seen many times before.

The transformative power of finance.

As markets climb higher and higher, or, as Wall Street says, “When the Bull starts to run,” it has an intoxicating effect for all involved. For investors, it gives them a feeling of invincibility, as if they have magically discovered the key to all wealth, no less, for the nation’s corporate managers.

Those executives who sit in “mahogany row” begin to feel that they, too, have discovered the answer to endless profit. CEOs and CFOs who began as experts in a given field suddenly feel they can manage any enterprise because they’ve found that “key” to wealth and success.

This feeling of invincibility, described by the ancient Greeks as “hubris,” often leads to the same tragic end Homer described long ago — portfolios decline, corporate profits fall, and, overall, the nation’s wealth declines.

In 1972, I saw this equation vividly at the annual meeting of one of the most popular companies of the day. Investors touted this company’s stock as a “one decision” stock. All you had to do was buy the stock, sit back, and watch your profits roll in. Ling Tempco Vought (LTV), the one-decision stock, a “sure thing,” a “can’t lose” company that everyone should have in their portfolio. Along with 49 other stocks like it, Ling Tempco Vought was part of the “Nifty 50,” fifty companies that were sure winners, bound to reach higher and higher plateaus of prosperity and wealth. And it was mainly the Nifty 50 that people cheered on that November day in 1972 when the Dow passed 1,000.

What many Ling Tempco Vought (LTV) investors missed, while the Dow climbed to the stratosphere, was that LTV, the company, was struggling, barely keeping its head above water.

Now, there are three things that every corporate manager, especially of a public company, must be aware of at all times: First, their market, the customers that purchase their goods or products. Secondly, the manager must be aware of the cost of capital, particularly if the firm has substantial corporate debt. Finally, the manager, whether the CEO, CFO, or any other corporate officer, must report to investors an honest, forthright accounting of their latest results.

As it turns out, LTV would fail on the last two of those requirements.

The Cost of Capital

The first of LTV’s executives to fall was James Ling himself, the founder and CEO. For 23 years, Ling had guided LTV to a series of dizzying successes. He had managed the expansion of LTV into sectors such as aerospace, airlines, steel manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, sporting goods, and meatpacking. All done through corporate acquisitions, most of which are funded by additional corporate debt.

It’s that last point that’s critical, as it was the reason the LTV Board relieved him. The late 1960s through the 1980s were a period of extreme debt volatility. The Federal Reserve whipsawed interest rates at an alarming rate. And it was those same interest rates that made the difference between a highly profitable LTV acquisition and a losing one. Ling was caught in the middle of these ups and downs.

From the time James Ling founded the company in 1947 until the mid-1960s, short-term (Fed Funds Rate) interest rates in the US were reasonably steady at around 4%. However, in what must have seemed a shot from the blue, in the summer of 1967, the US Federal Reserve embarked on its most aggressive interest rate hikes ever. From a low of 3.9% in July 1967, the Fed raised rates to 9.2% over the next 24 months. Consequently, borrowing rates also tripled. For Ling, this would mean the finance charge on his acquisitions suddenly tripled. A million-dollar loan would go from $30K per year to $100K.

Ling’s portfolio of highly profitable corporate subsidiaries was not losing money after finance charges. Someone had to be blamed, and it was Ling. In 1970, he was forced out, the first casualty of a nifty ’50 corporate calamity.

The Circle of Competence

Around the time James Ling was packing his bags at LTV and returning home to Texas, two young entrepreneurs were founding an investment company that would become one of the most successful of its kind. Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger founded Berkshire Hathaway in the early 1970s and developed the concept of the “Circle of Competence” as one of their chief value criteria.

Briefly stated, Buffett and Munger would invest only in companies whose management had demonstrated competence in their field. You may have noticed that, in addition to electronics and aviation, LTV added a Sporting Goods division and a meatpacking company when it acquired Wilson & Company.

For me, the reach of LTV’s aquisitiveness culminated in an amusing conclusion in the fall of 1973. I was then a stockbroker with EF Hutton and decided to attend the LTV Annual Meeting. In an effort to boost their stock price, Brokers were often invited to attend the Annual Meetings. I just gave the receptionist my business card and was ushered into one of the most amusing such meetings of my career (and I’ve been to more than a few).

Paul Thayer was now the CEO, a distinguished former test pilot and aerospace executive, and later served as the U.S. Under Secretary of Defense. Thayer was immediately put back on his heels as an angry crowd of investors demanded to know why their stocks had fallen so sharply. One particularly irate investor reported that his stock, at around $3, was worth less than LTV’s dividend had been just a few years earlier.

To understand what happened next, you have to know the makeup of these LTV Investors. Beverly Hills is home to a large Jewish population. Three-quarters of the attendees that evening were Jewish. In an effort to mollify the crowd, Thayer then invited them to receive a gift, prepared especially for them: a Wilson canned ham! As you can imagine, this Kosher audience didn’t think much of Thayer’s gift.

Conclusion

As we look back at the 142 years since Charles Dow invented the Dow Jones Industrial Average on July 3, 1884, we see the “mountain chart” of progressively higher investment records. Each generation builds upon the work of those who came before. It’s a visual representation of the country’s financial progress. Admittedly, one with some mistakes and hardships, recessions, and even depressions.

After all, even in the finest of corporate results, sometimes we deliver a “ham.”

Follow me here on ValueSide for more articles like this one.